Lake Huron, with its infinite islands and varied shorelines, ranging from long sand beaches in the south, to crazy granite and quartzite in the north, to the limestone flowerpots and bluffs and alvars of Tobermory and Manitoulin, has always struck me as way more enticing and unique than Michigan, Ontario or Erie, but also more hospitable and navigable than its more voluminous sibling to the north.

Huron has no big cities on its shore, unless you count Sarnia. It has dozens of lighthouses, and tens of thousands of islands, including, of course, the world’s largest to be found in fresh water.

The first European to set eyes on Lake Huron was presumably Samuel de Champlain, after navigating the French River to its mouth in 1615 (it’s possible that Etienne Brule got there earlier, but no precise record exists of his travels). Here, Champlain encountered a group of natives who were gathering blueberries; natives, as it happened, from Manitoulin Island.

A few decades later, in 1649, the Huron Nation (from which the lake derives its name,) and the fort established by the French at St. Marie among the Hurons, were routed by the Iroquois in the present-day Midland area in southern Georgian Bay.

Mantioulin’s first Jesuit mission, begun in 1648, was promptly abandoned after these Iroquois raids, and the Island’s Ojibwe and Odawa population scattered far and wide. It wasn’t until the early 1800s that Manitoulin natives returned, and a new mission was established in present-day Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory.

One of the Island’s more mysterious and sensational events occurred in Lake Huron waters off Wiikwemkoong in 1863. A corrupt fisheries commissioner named William Gibbarb, much loathed by the local first nations people, disappeared while returning to Manitoulin on board a steamer named the Ploughboy; his body was found floating in the lake three days later. No one was ever charged, but people in Wiky have an idea about what might have happened to this day. The story lingers on as “ The Manitoulin Incident” and 20 years ago Wiikwemkoong playwright Alanis King created a play from the story that was presented by the Debajehmujig Theatre Group.

The greatest loss of life on the Great Lakes for its time also occurred in Lake Huron, not far from Manitoulin. In 1882, the poorly designed and overloaded steamer Asia foundered en route to Manitowaning in a storm, killing all but two of its 144 passengers. One of the survivors was Dunk Tinkis of Little Current; the other was a young woman named Christine Morrison. The two teenagers, strangers to one another, but both, uncannily enough, 17, drifted to an island near Pointe Au Baril on a lifeboat, and were discovered the next day by a native couple. There is a monument to the event at Dunk Tinkis’ burial place in the Holy Trinity Cemetery just outside of Little Current.

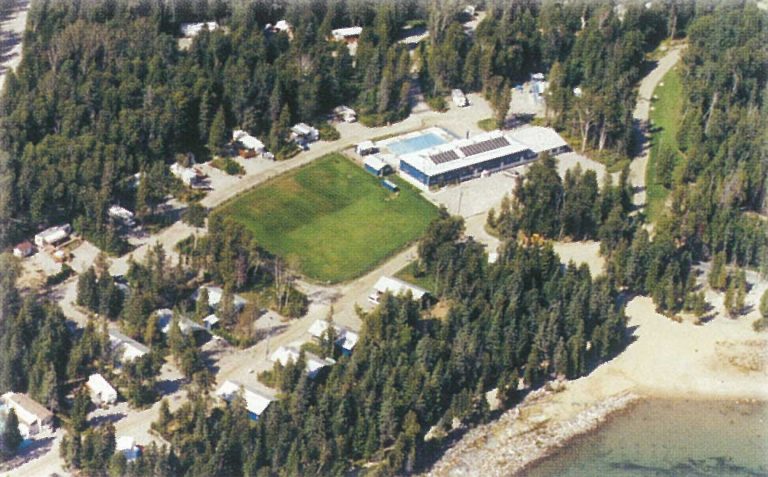

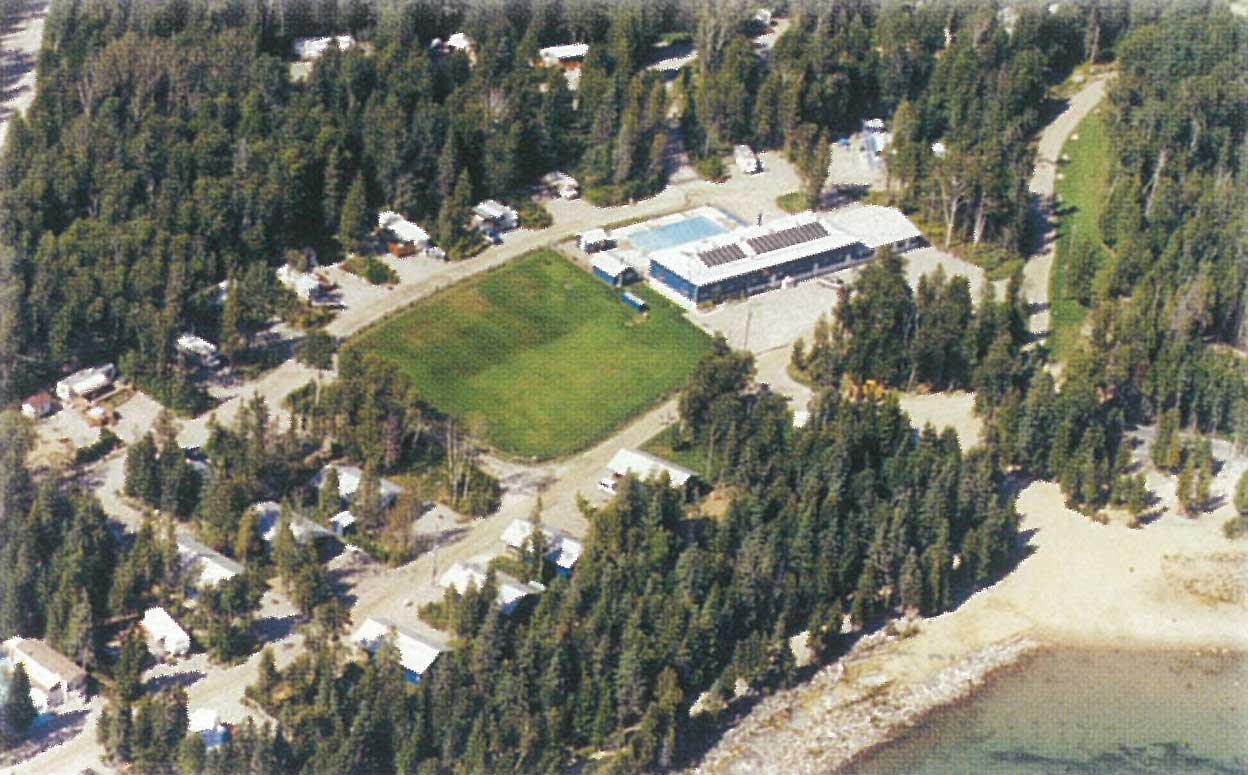

As I pulled into Providence Bay, parked, and got out to wander around on the beach, it was hard to imagine the sort of storm that might sink a boat the size of the Asia (136 feet). There was a brisk wind blowing this day, but it was out of the north, so the bay was quite calm, and the sun was bright and warm.

The beach at “Prov,” as the community is locally and affectionately known, is certainly one of the Island’s most popular spots, and deservedly so. But having never been the sort of person who likes to laze around on a crescent of sand, possibly exposing himself to skin cancer, I kept my tour short, and then headed for one of my favourite places on all of Manitoulin, the rocky east shore of the bay.

I parked at the marina, and started hiking down this rugged, scenic coast, striding over deep cracks in the fossil-strewn limestone slabs, tiptoeing across wave-smoothed stones, occasionally leaving the tread-marks of my boots in small pockets of sand.

Eventually I reached the light of Providence Point. It’s an unmanned light on a tripod tower. Just in front of it, though, you can see the foundation of the original lighthouse which once stood here.

According to the book Alone at Night, the “Prov” lighthouse was built in 1904 and was manned until 1953. In 1973, it mysteriously burnt to the ground. Some believed it was struck by lightning, but nobody seems to want to name names. The general theory, though, is that it was a local person who had some sort of gripe with the government.

After standing on the foundation of this lighthouse, gone now almost 50 years, I started hiking back to the marina.