By Isobel Harry

Manitoulin’s south shore, from Providence Bay in the Municipality of Central Manitoulin to South Baymouth in Tehkummah Township, is a delight to explore: multiple rural side roads and concession roads lead bicyclists and motorists on a merry chase down to beaches and lakeshore sand dunes, through idyllic pastoral land- and river-scapes dotted with century farmhouses and barns.

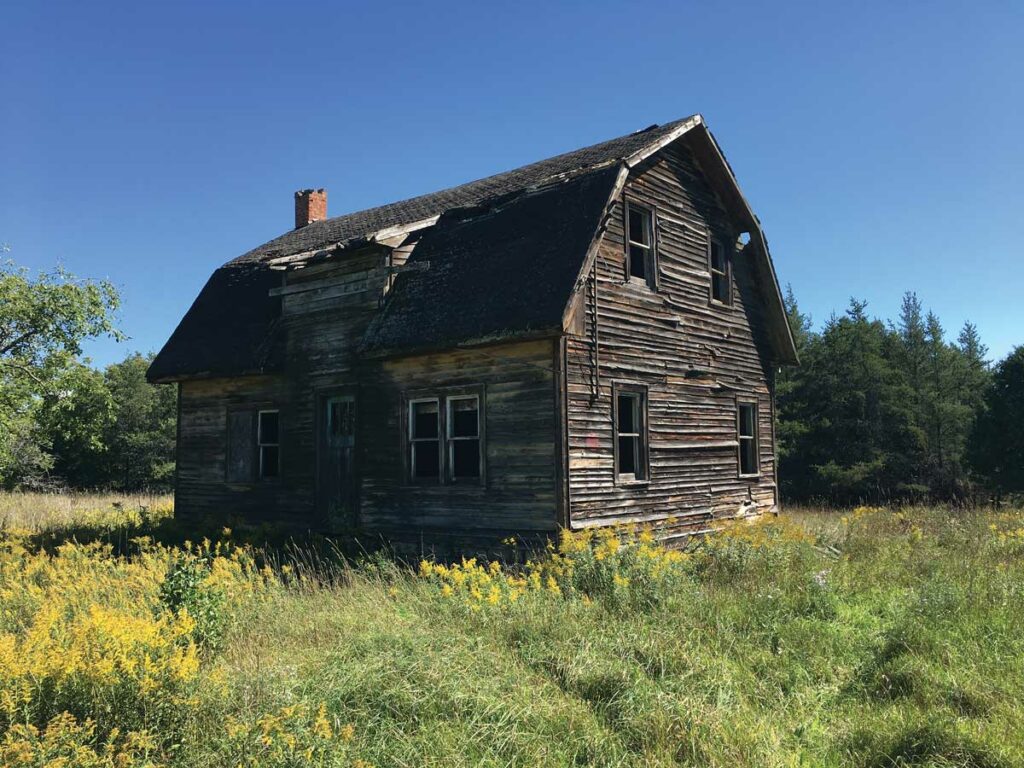

A closer look around at the early homesteads of the settlers who arrived on Manitoulin’s Lake Huron coastline after the still controversial Manitoulin Treaty of 1862 reveals much about how they coped with the rigours of settlement. The wooded and rock-strewn land was painstakingly cleared for farms, gardens and livestock and the first rough shanties and small log cabins built for the families that would grow there. These first structures later became outbuildings, many still in use or barely standing, when money allowed for the construction of a “proper” wood frame home, usually one and a half storeys high.

A good example of two styles on Highway 6 near South Baymouth. Gambrel roof home with a shingle-sided addition. Photo by Isobel Harry.

This early farmhouse style is seen everywhere on Manitoulin and indeed in all of Ontario – variations on a small wood frame home with a steeply pitched roof, a central entrance door in front with a ‘pointy’ gable and dormer window or transom over it and two evenly-spaced windows on either side. The style first gained popularity in 1865, when the Canada Farmer magazine published the architectural plans for the “ideal home” for a small family, known as the Ontario Gothic Revival Cottage, The wide use of these plans over one hundred and fifty years ago ensured that the style has become almost synonymous with settler architecture – it was the most common residential design in all of Ontario prior to the 1950s.

However, in the early years of settlement in remote rural regions such as were being established on the Island’s south shore, necessity became the mother of invention and gave rise to uniquely functional home building styles. Without architectural degrees or the expense of ordering plans from a magazine, many settlers built homes of their own devising, better suited to their often straitened economic circumstances, the available supply of local builders and materials and the climate and locality. This type of construction is called vernacular architecture, buildings by and for local people, using what’s on hand locally, according to needs and means.

Here, in Manitoulin’s south shore townships, that often meant putting up a small square stone or wood-framed one- or one-and-a-half storey house with a gambrel roof – no pointy gables here, no decorative flourishes. The gambrel roof, often called a barn roof or hip roof in these parts, was the choice of many homesteaders in those days. Adapted from capacious barn roofs, it provided much more room under the eaves than the usual Gothic-style roof with its steep sides.

A rural ramble along Government Road yields many examples of the use of the practical, space-enhancing barn roofs topping newer or antique homes, a phenomenon exclusive to the Manitoulin south shore. While popular all over the Island on barns and outbuildings, here the barn roof defines a micro-local home building trend that is fascinating to discover.

One of the oldest existing homes in this style is the stone house built “during the Depression years” (1920-30s) by Archie and Hazel Brown on the 15th Concession in Tehkummah. This is the grandparents’ home of Gary Brown, himself a builder, son of Carl who built Carl’s Trading Post in South Baymouth in the 60s, the gas bar, garage, convenience store and unofficial visitor information centre known to all in the ferry port.

Now unused by the farmers who till the fields around it, and despite its disrepair, the house has an air of unmistakable solidity, squarely set into the ground on its stone walls. Here was a humble and heartfelt effort to provide shelter from the elements, a place for children and animals to thrive – the texture of time etched into the stones. Archie and Hazel Brown’s house was considered large at the time, says their grandson. On the second floor were three bedrooms, a washroom and “a little music room at the top of the stairs” where the gramophone waited to be cranked up of an evening.

“All the materials were from around here,” says Gary Brown. “The stones came from the Overfield quarry or from the bush. There were other quarries and quite a few sawmills, in Tehkummah, Michael’s Bay, Sandfield area – there were options.”

Mr. Brown recalls the many gambrel-roofed homes he built in the area as the owner of Gary Brown Construction, pointing this way and that, up the road and across the township, listing homes built without formal plans, featuring the distinctive roof.

“It’s a popular style because these types of houses are easy to build,” he explains. “You put the ground floor in first so you can stand on it to erect the walls. The homes are usually small, sturdy and easier to heat because the warmth rises up the middle through vents; the barn roof saves on siding, too, because it comes down over the house, which also helps keep it warm.”

Down in the community of Snowville, Anne Leeson, the daughter of one of Tehkummah’s best-known local builders, still lives with husband Lorne under the gambrel roof of the family home. Her late father, John Blackburn, a stonemason and builder, constructed the sturdy stone residence in 1948, across the road from the original house of the community’s founding Snow family.

Settled sometime in the late 1860s or early 1870s and tucked into the township’s northwest corner off the Townline Road, Snowville once had a store and a post office to serve the busy little farming outpost.

“Mom and Dad raised three girls here,” says Ms. Leeson, as we look around the tiny, tidy ground floor layout comprising the kitchen, dining and living rooms built by her father. “Everything is trimmed in black cherry, including the archways and the built-in cupboards that my dad fitted in instead of closets; many houses didn’t have basements, but we had one, with a furnace. Dad put vents in the ceiling so the heat could get up to the bedrooms under the roof. It’s always cozy in winter.”

Among the family photos are some glossy black and white prints by the late South Baymouth photographer, Art Gleason, who seems to have had an eye for local architecture. Anne Leeson recalls that her dad’s stonework was meticulous: “He would hand cut the rock, and never used rusty stones,” she says of the limestone that can sometimes show stains from iron deposits. “The stones never need patching; he also made headstones and gateposts.”

Mr. Brown started his building career “as a kid,” by helping John Blackburn with stonework: “He was a big man, he chipped the rocks and I laid them,” says the man who went on to build Brown’s Restaurant and many homes in South Baymouth. “All the places I built with John Blackburn were in that style. The stonework kept the house warm.”

In those days local hand-built lime kilns fulfilled the key function of burning limestone into powdered lime to be added to stonemasons’ mortar. Lyle Dewar, farmer and retired delivery mainstay for forty years with the old McDermid’s hardware store in Providence Bay, recalls: “There were many lime kilns in this area; my father had a lime kiln. It would take 25 cords of cedar burning stone for five days and four nights to make the lime that would be mixed with cement, mostly for barn foundations, barn stone floors, chimneys and homes.”

Because of the extreme heat required to burn the stone, fires had to be tended night and day, sometimes leading to raucous parties around the kilns. No longer in use, they long ago crumbled into the ground, but a keen eye, alighting on an overgrown mound, perhaps, a scattering of bricks or stones, might catch a glimpse of these elderly sentinels of the settler era.

Only a small vestige of this thriving industry remains, near Sheguiandah in the Town of Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands (NEMI), where the Island’s first peoples began quarrying the area’s quartzite for tools and spear points after the last Ice Age, over 10,000 years ago. A trip along Sheguiandah’s rolling, picturesque Townline Road from Highway 6 ends at Lime Kiln Road, marking the site of an old kiln here, overlooking gorgeous views down to Lake Manitou. A new quarry has started operations here in the last few years, carrying on the local tradition of millennia as the Lime Kiln Quarry.

“There were lots of stonemasons around then; these guys cracked stone like there was nothing to it,” says Mr. Brown. “Builders were pretty quick, too, they’d put up a barn in a day. Boards were nailed, not power-nailed; we used string to line things up, not lasers; materials were better, roofs thicker – a roof would take a whole day to burn, not an hour like today’s houses,” adds the veteran member and past fire chief of the all-volunteer Tehkummah Fire Department, somewhat wistfully.

No-one on Manitoulin’s south shore ever called what they were building “vernacular,” or anything of the kind. Nevertheless, a wander along here rewards with many opportunities to imagine the stories of its built structures – simple, unadorned (and now, sometimes almost falling down) yet esthetically pleasing repositories of regional history and culture, genuine manifestations of the environment, its people and its history.