By Isobel Harry, This is Manitoulin 2021

The morning of the long-awaited excursion is wet; rain, misting at first, turning into a soaker. Nevertheless we persist, unlocking the newly-installed metal gate off an unremarkable lane in the village of Sheguiandah and closing it behind us.

Ahead, a newly-built boardwalk and sets of stairs climb the gently rising escarpment until they vanish into the forest. We are entering the Sheguiandah National Historic Site of Canada, one of the oldest archaeological sites in the country, open this year for the first time ever to the public: Spring 2021.

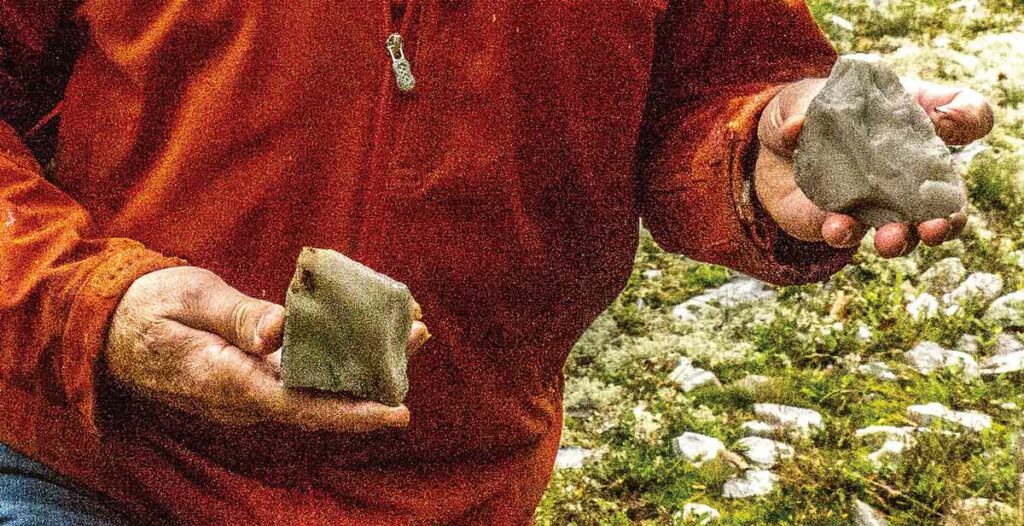

The earth beneath our feet was laid down 450 million years ago, in successive layers over millennia, on top of what had come before, the two-billion-year-old quartzite bedrock of the Canadian Shield, or Precambrian Shield. On Manitoulin, quartzite is visible in only a few places, in high spots, usually, where the brilliant white rock was the only landform standing above the waters of glacial Lake Algonquin (ancient Lake Huron) over 10,000 years ago. As the waters receded at the end of the last Ice Age, sediment covered the rock below the water line, leaving exposed knobs of quartzite behind. It is then that the Island’s first inhabitants arrived here, moving north as the glaciers retreated and water levels fell, drawn by the glinting white stones’ great utility in quarrying for tools and spear points.

Guiding a sneak preview of the upcoming site tours (pending pandemic conditions) is Dr. Patrick Julig, the geo-archeologist of Sudbury’s Laurentian University who, in 1991, along with Dr. Peter Storck of the Royal Ontario Museum, re-opened the long-abandoned excavations first dug by Dr. Thomas Lee in the 1950s. The team analyzed thousands of found stone implements and geological samples and carbon-dated the site to 10,000 years B.C.E., or about 11,000 calendar years ago.

“The heritage value of the remains found in Sheguiandah,” reads the Canadian Register of Historic Places, “resides in a series of successive cultural occupations of early inhabitants in what is now Ontario, beginning circa 11,000 B.C.E. with the Paleo-Indian Period during the recession of glacial Lake Algonquin. The site also contains artifacts from the Archaic Period (1000-500 B.C.E.) as well as Point Peninsula Culture stone tools associated with the Middle Woodland Period (0 – 500 C.E.).”

The Sheguiandah site offers the thrilling opportunity to experience these ‘successive cultural occupations,’ one after the other, on a guided tour.

“We are walking back in time,” says Dr. Julig as we begin our ascent, describing our trek upward through a series of ancient beach terraces representing different cultural periods, based on the tools and other artifacts found here and on analyses of the earth’s layers.

Earlier, during our orientation in the gazebo at the edge of Sheguiandah Bay, Dr. Julig pointed to the treed escarpment that lines the other (east) side of the bay to explain the beach levels corresponding to different eras that are clearly visible as “steps” in that ridge. The natural landform is a geological record of the ancient glacial lake waters receding through time – remaining at one level for thousands of years, carving a step, or beach, into the ridge – down to the modern water levels we know. Similarly, as we go up the Sheguiandah site hill, each new beach level is higher and older geologically than the last, ending with the oldest part of the site at the top. These older and successfully newer sites correspond to the historic access to the quartzite, from the water, as the ice sheet gradually melted and, over time, access was gained to lower and lower sites.

From the edge of the bay to the trailhead, just a few hundred yards up a low rise, we have already gone back in time 2,000 years, to the first ancient raised beach terrace on this walk (or the last, and earliest, if you count back from the oldest, top level), the 2,000-year-old Algoma water level. Here lived nomadic people known in anthropology as ‘Late Woodland,’ tribes that traded copper goods, shells and flint tools, made pottery pipes and vessels, baskets and worked hides.

The beach levels are highlighted in a series of 12 explanatory plaques along the boardwalk, as are the corresponding periods of human activity, offering a rare ‘living lesson’ in the prehistory of Manitoulin Island as we walk. “The people kept coming back here to work the site,” says Dr. Julig. “They first arrived to work the quartzite at the top and as more and more land became exposed as the water lowered to the present-day levels over thousands of years, succeeding groups of nomadic people arrived to quarry and live here for brief periods.”

Accompanying us is Heidi Ferguson, economic development officer for Northeastern Manitoulin and the Islands (NEMI), who has worked with the municipality, landowners, the Archaeology Division of the Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries and with some First Nations chiefs and Dr. Julig for several years on bringing the development of the site to fruition. Both Ms. Ferguson and Dr. Julig underline the importance of conservation in the planning, building and ongoing use of the site. “The site is very sensitive to disturbance,” says Dr. Julig. “We ask visitors to stay on the boardwalk, to protect the ancient artifacts.”

“We continue preserving, studying and exhibiting collections of artifacts that tell the story of the Anishnabek and earlier Indigenous cultures that quarried, camped, fished, hunted, gathered and traded around Sheguiandah Bay,” Ms. Ferguson adds.

For history, geology, anthropology and archeology buffs, hikers, lifelong learners and kids, the Sheguiandah site is a magical place of wonder. The forest provides a leafy backdrop to contemplation and imagination as we rise through the millennia. We move up to the Nipissing beach terrace as Dr. Julig explains the ancient seasonal uses of certain plant species for medicines, dyes and foods including rare-for-Manitoulin blueberries found here in the more acidic soil around quartzite. This beach level, the archeologist says, dates to around 5,500 years ago, and evidence of people of the Archaic era—large quartzite bifaces (the beginnings of their distinctive notched spear points)—has been found near here.

Upward we go, ever farther back in prehistory, reading about fossils found in the 450 million-year-old Mystic Ridge area, learning from Dr. Julig’s intimate knowledge of the site since the ‘90s and of the controversies surrounding the dating of the site since the 1950s. The relatively flat ‘Habitation Area’ is the site of the first excavations of Dr. Lee. Here, in these shallow rocky pits, the scientist found the knives and scrapers that would have been used in a camp or habitation area, animal bones, pigment of the ‘Late Paleoindian’ period, when humans first appeared in the archeological record in North America.

By the time we reach the top, the immensity of what we’ve just experienced as we time-travelled up through this silent forest of ancient secrets is finally felt. We seem to exhale all at once, standing here on the fabled quartzite, eyes tracing the gently sloping landscape as it glides down to Sheguiandah Bay and the Modern Era.

The approximately one-hour-long guided tours can be booked in advance at the Centennial Museum of Sheguiandah or online.

An interactive exhibit with site artifacts may be viewed at the Museum.

For updated information, visit www.shegsite.com

The Centennial Museum of Sheguiandah

10862 Highway 6, Sheguiandah.

Tel: 705-368-2367

Open May to October.